Akitaka Yamada

Osaka University

Akitaka Yamada

Osaka University

When examining linguistic variation, it is important to detect the factors affecting selection tendencies. For example, selection tendencies may change per verb (a linguistic factor) or per register (a social factor), while some are attributed to sentence-level factors, and other idiosyncrasies are ascribed to no clear factors at all. Thus, when only personal introspection is used, proofs concerning how far each of these many factors contributes to a selection become less convincing and objective.

To separate lexical idiosyncrasies from general tendencies, this research promotes a corpus study employing an underused statistical model: the Multinomial Mixed-Effects Model (MMEM) (Leshvina, 2016). Applying this model to variations among Japanese subject-honorifics, this study shows how scrutinizing random effects reveals lexical idiosyncrasies and contributes to the discussion in theoretical linguistics.

Japanese has several subject-honorifics, as illustrated in (1), and how they differ in use is of great concern.

(1) a. sensei-ga go- tootyaku-ni nat-ta.

teacher-NOM HON-arriving-ni become-PST

b. sensei-ga tootyaku-nasat-ta.

teacher-NOM arrive-hons-PST

c. sensei-ga go- tootyaku-nasat-ta.

teacher-NOM HON-arrive-hons-PST

‘The teacher arrived.’

Previous studies have revealed that (HYP 1) a verb of one mora cannot be used with the honorific prefix, and (HYP 2) a verb of Chinese origin favors the nasar-construction when compared to the go…ni nar-construction. Our goal is to examine to what extent these well-accepted conclusions are supported by the real corpus data.

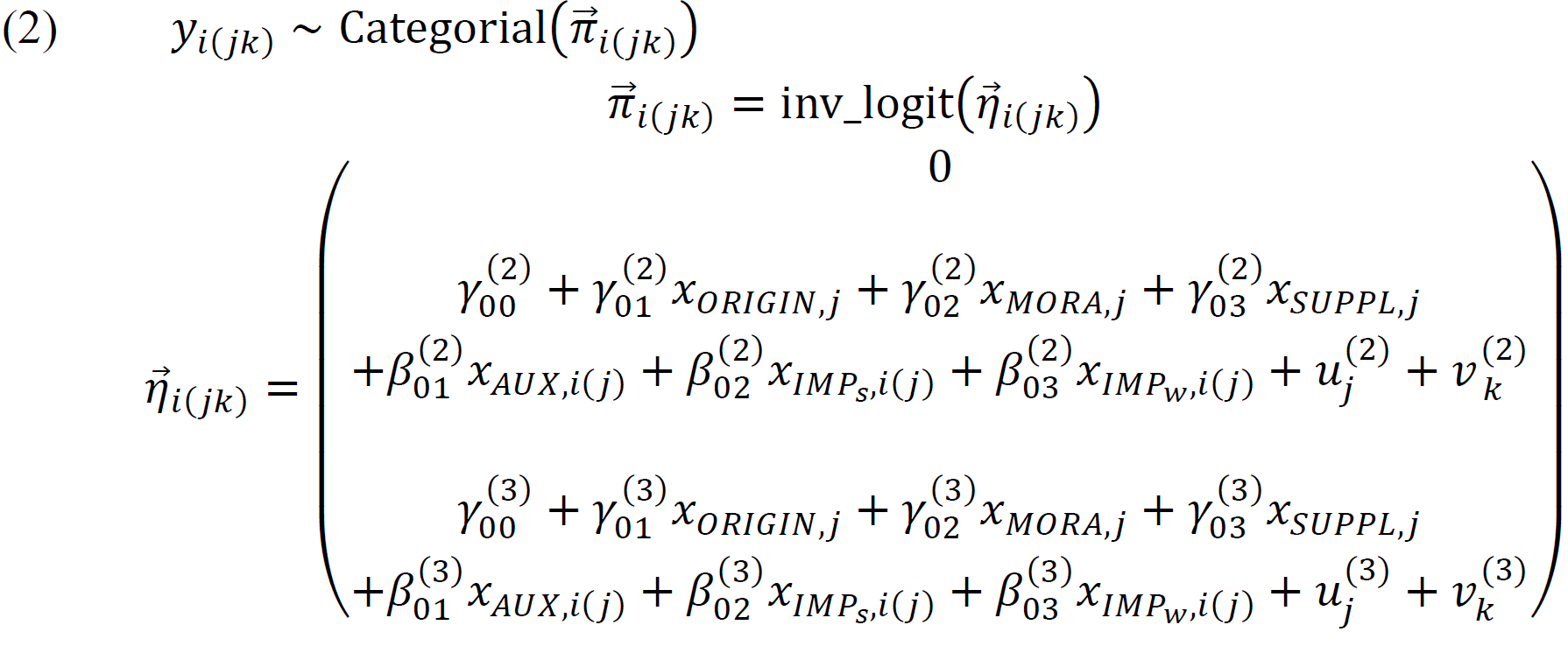

The data set is a sample from the BCCWJ. Among the 20,864 hits, we concentrate on verbs used at least more than 24 times, because it is not easy to detect the distributional profile of a verb with a lower frequency. Based on these 11,223 cases, the study builds the following MMEM model by developing the model proposed in Yamada (2019a):

The outcome variable is the choice of subject-honorific constructions in (1); the go…ni nar construction is set as the baseline category; γ⃗(2) and β⃗(2) represent the construction in (1b), and γ⃗(3) and β⃗(3) represent the construction in (1c). The considered predictors are as follows:

(3) Group-level fixed effects:

a. SUPPL: 1 when the main verb has a suppletive form; 0 otherwise

b. MORA: 1 when the main verb is formed by one mora; 0 otherwise

c. ORIGIN: 1 when the main verb is a word of Chinese origin; 0 otherwise

(4) Population-level fixed effects:

a. IMPs: 1 when the sentence is a strong imperative; 0 otherwise

b. IMPw: 1 when the sentence is a weak imperative; 0 otherwise

c. AUX: 1 when the subject-honorific marker appears on an auxiliary; 0 otherwise

(5) Group-level random effects:

a. LEXEME: a grouping variable indicating the predicate to which the subject-honorific marking is attached

b. REG: a grouping variable indicating the register from which the sentence is taken.

To avoid the problem of complete separation, we assume weakly informative priors N(0, 3) for fixed effect parameters, and Half-t distribution for the variance of random effects Half-t4(0, .5).

The Hamiltonian Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm is adopted to estimate the parameters of the Bayesian MMEM. Stan is employed on R, allowing allows us the No U-Turn Sampler. After confirming the convergence in estimation (with the R-hats of the estimated parameters being < 1.01), the posterior distribution is interpreted for each parameter.

Figure 1 illustrates the priors (left panel) and the corresponding posterior distributions (right panel); the light and dark gray regions represent the 95% and the 66% credible intervals, respectively. In general, the posterior means of the fixed parameters do not substantially differ between γ⃗(2) and γ⃗(3), or between β⃗(2) and β⃗(3), except for γ02(2) and γ02(3), in agreement with the view of (HYP 1). The γ01(2) and γ01(3) are also in line with (HYP 2). The IMPs shows the largest effect size; (1a) rarely takes the strong imperative form, while (1b/c) have no such restrictions (Yamada, 2019b). The positive value for AUX means that the construction in (1a) is not as easily used as an auxiliary as those in (1b/c) (Yamada, 2019a).

While the results of the fixed effects essentially coincide with the findings of previous literature, MMEMs also allow us to examine idiosyncrasies not attributed to the aforementioned structural/general tendencies. Observe the scatterplots in Figure 2, which show how each lexeme has its own lexical idiosyncrasy. The following findings are worth attention.

These findings show that the generalizations in (HYP 1) and (HYP 2) are not absolute rules, and can be overwritten by lexical idiosyncrasies. Although due to space limitations, this research refrains from providing an analysis, it will be important for future study to examine why these “outliers” exist. The fixed effects findings also require further investigation. For example, the interaction with an imperative is a legitimate concern, which would be better discussed from pragmatic perspectives (Yamada, 2019b). The issue of auxiliary status can also be approached via the grammaticalization theory. Whatever theoretical framework is adopted, analysis must be based on empirical facts. This topic cannot be approached without data analysis, such as that completed in this study, which provides descriptive desiderata and, thus, serves as a necessary departure point for theoretical investigations.

This work was supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (Start-up) #20K21957, and the NINJAL collaborative research project “Cross-linguistic Studies of Japanese Prosody and Grammar.”

Levshina, N. (2016) “When variables align: a Bayesian multinomial mixed-effects model of English permissive constructions.” Cognitive Linguistics, 27(2): 235-268.

Yamada, A. (2019a). “Competing subject-honorific constructions with predicates of Yamato origin [Wago kigen no doosi to kyoogoosuru sonkeigo koobun].” Proceeding of the 168th Meeting of the Mathematical Linguistic Society of Japan, pp. 66-71.

Yamada, A. (2019b). “An OT-driven dynamic pragmatics: high-applicatives, subject-honorific markers and imperatives in Japanese.” Proceedings of Logic and Engineering of Natural Language Semantics 16, pp. 172-185.